For our house is our corner of the world. As has often been said, it is our first universe, a real cosmos in every sense of the world. If we look at it intimately, the humblest dwelling has beauty. ~ Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space

The house and the face: the two subjects first drawn by almost every child. The house with its window-eyes and door-mouth, the face with its eye-windows and mouth-door, the house with its occasional plume of smoke curling around like a tendril of hair; the portrait of house and of face make up the two central concerns throughout life: people (family, friends) and a place of shelter.

Like the face, the house obeys the laws of time: it comes into being, it ages, and all too often, it ceases to exist. This is especially true in America, where wrinkles occupy retirement institutions (strange how we call them homes) and sagging soffits and porches are often signs of the upcoming teardown so prevalent in well-heeled cities today.

Emily Rapport’s recent body of work approaches the house as a subject of portraiture. In her paintings she addresses the role of the house as a humanizing factor in our life (it is where we live, love, argue, play, work, and age), as a construct of community (houses on any given block are superficially different from each other, and yet form neighborhoods where residents experience a certain sense of belonging and pride), and finally, Rapport unflinchingly portrays the changes in these same neighborhoods: the gutting, teardown, and rebuilding of houses, a process that often implies displacement for those at the bottom or in the basement of society.

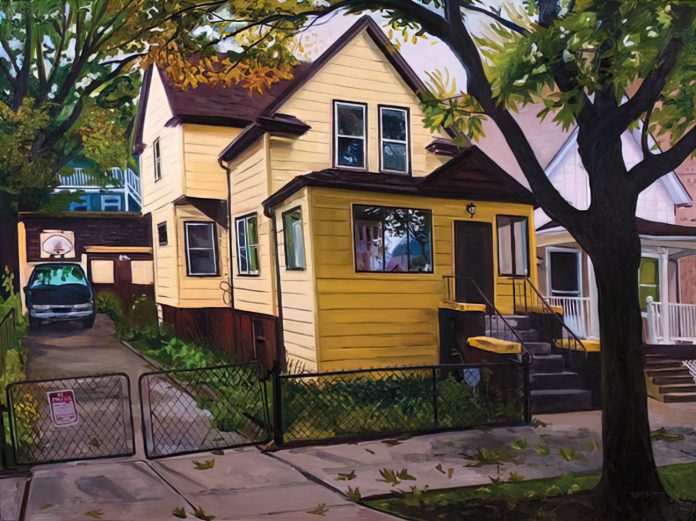

I am looking at The Yellow House, Brown Trim (top image). There is a house, a car, a Chicago-style garage that gives out to the alley (Note to New York City! This is where Chicago puts its trash! Not on the sidewalk!), vegetation, and a scrawny chain link fence. Let us look closer: there is a basketball hoop, a wire coming out of the side of the house, it juts out as if intent on escaping, like so many wires hastily added on to older homes for internet and cable, and a faded small sign meant to discourage burglars. The windows reflect back out on to the neighborhood: there is the reflection of a tree on city property, it is the iconic yellow maple that grows in a gangly sort of way, much like the teenagers who perhaps shot baskets there this afternoon, last year, or ten years ago. Then, there is the house next door: their porch seems pristine. Do the owners wish their neighbors would put on a better face?

Without seeing the inside, we sense that this is not just a house; it is a home. Children were raised here, parents have grown older, grandparents have visited, a dog or car has colonized the backyard, t.v. has been watched, illicit phone calls made, perhaps even an unsupervised party or two has occurred. This house has been the protective shell for those within it. As Gaston Bachelard writes in his magisterial work The Poetics of Space, “…the house shelters daydreaming, the house protects the dreamer, the house allows one to dream in peace.” In other words, the shelter of the house gives us the space to dream, to muse, and to do our homework. Those who struggle with rent or finding shelter, their dreams are all too often suppressed.

Johannes Vermeer, The Little Street (Het Straatje), 1657–58

The house has long been a familiar subject in painting. Vermeer’s The Little Street depicts a brick house on Vlamingstraat that scholars believe to have been the home of Vermeer’s aunt, who owned a business selling tripe. It is a solid house and solidly working class: the brick window headers are modest, paint is chipping away here and there, and the colors of the repainted window frames vary, indicating perhaps that whatever paint was at hand had been used for touch-ups. Children play, a small grey cat looks for a stray piece of raw gut next to the passage that was called Tripe Gate, a woman works on something in her lap (embroidery, maybe lace?): the whole scene speaks to being at home and being there solidly and with confidence during the Dutch Golden Age.

More recently there are the houses of David Hockney and Edward Hopper. Hockney’s focus on the abodes of wealthy Californians and their outdoor swimming pools, the painterly flatness referring to the dry Southern California weather and the relative flatness of experience or lack of struggle that most of these people (many of them his benefactors) had in their life. Hopper’s houses, despite often being painted in isolation, provide an interesting confluence with the houses included in this exposition. Hopper’s houses, like Rapport’s, use architectural details (porches, balconies, posts, box windows, cornices, and siding to mention just a few) as so many facial details (make-up, piercings, moustaches, moles, sallowness, ruddiness, noses, fixed or not) that customize both the house and the face; details that are universal and immediately recognized and yet have limitless variations as they decorate, beautify, and render unique. As an example, look at Rapport’s Duo-Tone House, which is actually a three-tone house thanks to the beautifully rendered turquoise tree shadow fingering across the olive facade. What architectural fantasy, some would say emboldened madness, prompted its owners over the years to build a large box-like extension that juts out and covers up the classic A-frame? Like a botched face-lift, the original forehead peeks out from behind this large, unbalanced add-on that took place, one must imagine, due to a growing family and a wallet not fat enough to hire an architect, while the mismatched blue and green siding remind us that the concept of making due with what is on hand has not changed much since Vermeer’s tripe house in Amsterdam: practical decisions in practical neighborhoods, preceding the contagion of discarding and tearing down, often known as development.

Emily Rapport, Duo-tone House, oil on canvas, 30″ x 40”

This brings us to another human concern in Rapport’s current work: the transient nature of the American urban home. Rapport works in Ravenswood, Chicago, a neighborhood that has been affected by the teardown trend in the city of big shoulders. Teardowns tend to replace affordable housing with expensive condominiums or large, very pricey homes, escalating real estate prices and pushing out working-class families and renters. The environment also loses out from the trend of demolishing homes: a substantial percentage of all landfill in the United States is construction and demolition waste. When chronicling changes in neighborhood housing, Rapport often chooses to focus on the gentler urban idea of renovation, for if tearing down can be construed as an end, then rehabilitation is what we do after a set-back: we try to combat what ails us or attempt to turn around the relentless march of time. This is no less true with houses. Too small? It can be enlarged. Leaky roof? It can be replaced. Seventies kitchen in avocado or harvest gold? It can be transformed. In a series of four paintings, Rapport takes on the rehab of a house on Wolcott. Again, like in many of Hopper’s houses, there is a dizzying richness in detail that invites the viewer to look closely and patiently.

Emily Rapport, Summer’s End, oil on canvas, 24″ x 36”

I would like to focus on the first and third in the series, both painted at dusk, a time of day that Rapport particularly excels at. In the first one, Summer’s End, a small A-frame, rather dwarfed on one side by a much larger house and on the other by a brick two-flat, is portrayed in a dilapidated state: much of the siding has fallen off, exposing the wood of the frame. Rapport’s use of burnt umber, chestnut, and black conjure up the sensation of wetness and the smell of mildew: anyone how has lived through a renovation and has seen and smelled old wood lath knows exactly what I am describing. The porch is falling apart, the yard is overgrown and littered with parts of itself, similar to an old person who has inadvertently soiled himself, and my favorite detail: two perfectly functional chairs in the midst of all this disarray. And the coke cans, like barnacles on a ship, cling to the chairs as a reminder that life still exists in this yard, despite all the other signs that say otherwise.

Emily Rapport, Raising the Roof, oil on canvas, 24″ x 36”

In the third of the series, we see the same house in a state of transformation, partially wrapped in Tyvek, that ubiquitous subdermal layer under most rehabs or new constructions. Gone are the vestiges of disrepair: this is a zone of activity and of becoming. Piles of two by fours are strewn around the wet yard, two large bins for trash are the left side, and the roof rises hopefully into the dark blue summer sky. To the right of the house-in-progress is the same two-flat that in the first painting seems to be giving the A-frame a hug of encouragement. In this painting, it is the main source of light, glowing and illuminating the whole composition with yellows, oranges, and reds coming from the uncovered bulbs on the porch, and casting a beautiful, perfectly still shadow of itself into the puddle of muddy water. It is an urban, secular glow, not one of whispers but of shouts, not one of immortality and grandeur, but of the here and now, of baseball games, transistors, children yelling, dogs barking, crickets, and neighbors talking in the warm, summer night.

Rapport’s artistry lies in finding the beauty in these scenes; in the average, mundane moments all of us live. She suggests that our gaze, when finely tuned and alert to our own urban landscape, can bring us wonder and beauty while walking past a two-toned house, a Walgreens pharmacy, or a construction site. To borrow from Nelson Algren (whose house on Wabansia was torn down to make way for the Kennedy Expressway), these paintings are “like loving a woman with a broken nose. You may well find lovelier lovelies. But never a lovely so real.”

Top image: Emily Rapport, Yellow House, Brown Trim, oil on canvas, 30″ x 40”

About

Emily Rapport studied painting at The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art in New York (94-95), and received her BFA from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2005. Emily’s work has been exhibited in New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Amsterdam. She lives and works in Chicago.

Vicki Schneider is a Chicago-based writer and French teacher. She writes both serious articles (but not too serious) and humorous essays (but not too humorous). She’s from the Midwest, so she does not like to get carried away.