Michele Feder-Nadoff’s work spans a broad territory that includes drawing, painting, sculpture, video, installation, writing and performance. These seemingly diverse works share certain elements, including a preoccupation with surrounding, containing and activating empty space; investigating the way all of the senses combine in the activity of making, and in expanding her practice to involve cooperating and collaborating with diverse communities of makers.

A seminal experience for Dr. Feder-Nadoff, was her initial trip to Santa Clara del Cobre in Mexico in 1997, where she was accepted as an apprentice by a family of traditional coppersmiths. This led to a continuing relationship with that community as she returned year after year to work with and learn from them. This culminated in the publication of a book, Ritmo del Fuego/Rhythm of Fire and a documentary video Huele de Noche about Santa Clara, its people and culture. This also led her to pursue a doctorate in Anthropology at El Colegio de Michoacan, which she was awarded in 2017.

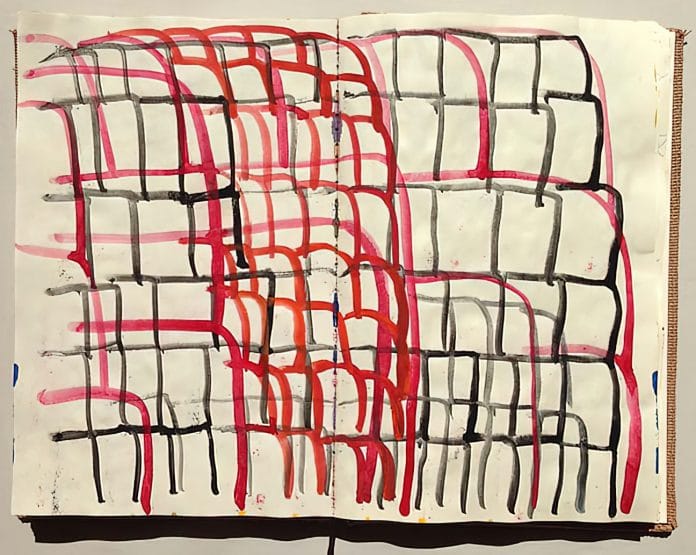

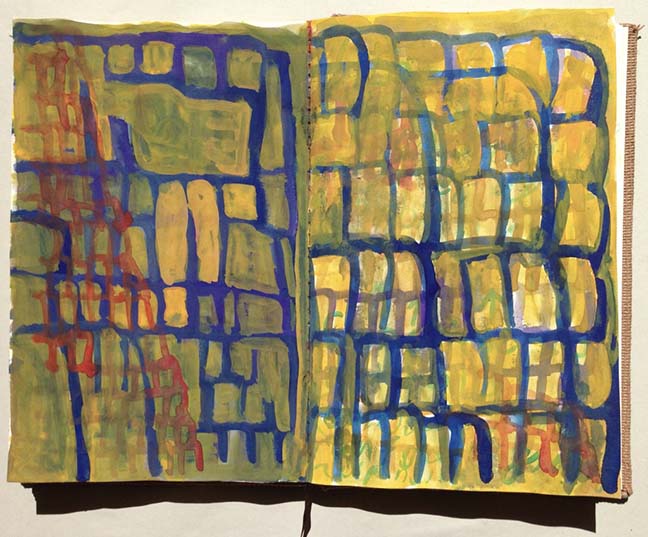

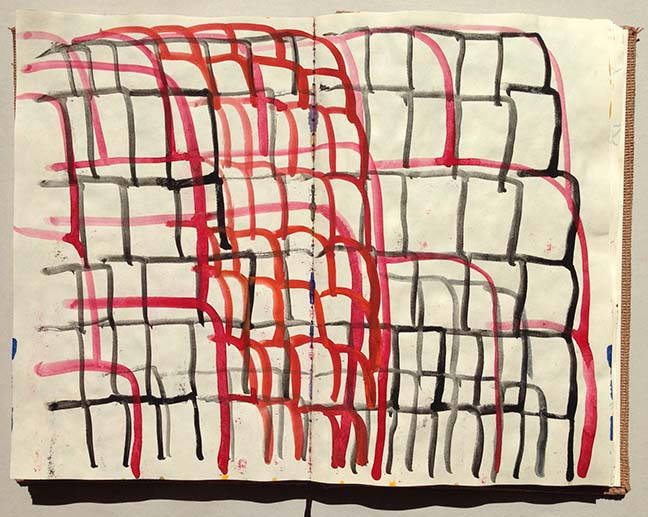

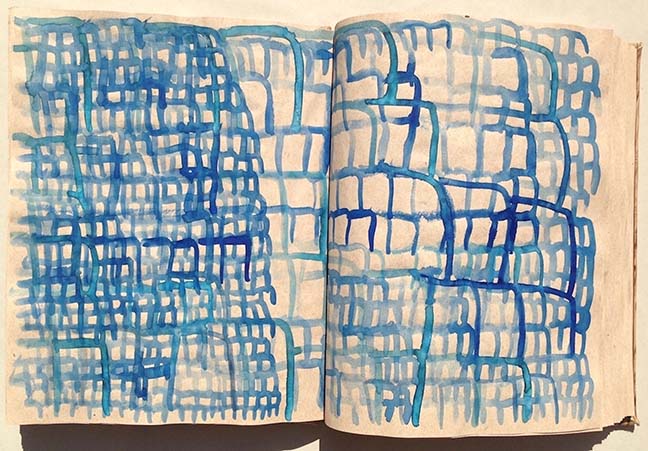

In recent years, she has been working on a group of meditative drawings, the Chayah series. These drawings allude to writing, and involve a sort of tunneling across the page, where movement and touch become as important as seeing. The marks she makes gradually become lighter as the brush runs out of paint, then a new line of marks is initiated. The process determines the structure to a certain extent. Intentionality combines with chance in producing the final outcome. She describes this method as like “the secretions of a snail or the tunneling of a mole:” the “mole theory.”

“Benjamin Notebook, 1,” gouache and sumi ink, from Chayah series, 8.5” x 10.75”, 2017

“Benjamin Notebook, 1,” gouache and sumi ink, from Chayah series, 8.5” x 10.75”, 2017

David Richards: You started out as a painter, what prompted you to begin making sculpture?

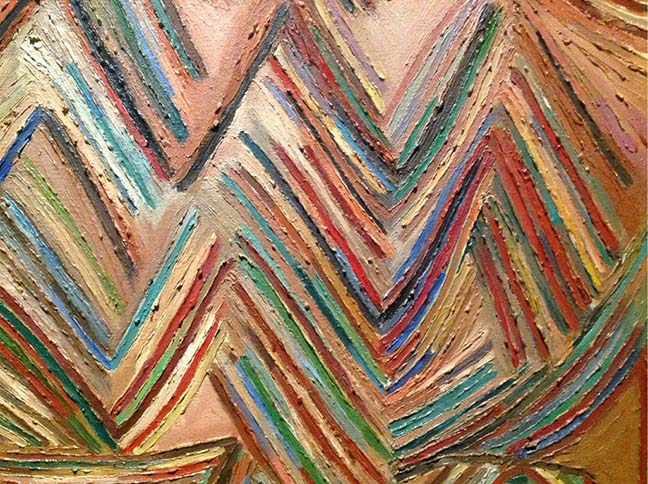

Michele Feder-Nadoff: I had worked in clay when I was younger, so it wasn’t that I was unfamiliar with sculpture. When I was doing paintings at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in the early seventies, my first mature body of work… mark making to me was always very physical and tangible. It wasn’t just representing an image on the canvas; it was about making something physical, a real thing in real space. The painting was always like an object to me, the surface was very organic, and I was conscious of how light was working on the surface and how things kind of grew. So I was always looking at painting both two-dimensionally and three-dimensionally.

Detail, “Chevron (Ray),” oil paint on stretched canvas, 40” x 32”, 1976

Detail, “Chevron (Ray),” oil paint on stretched canvas, 40” x 32”, 1976

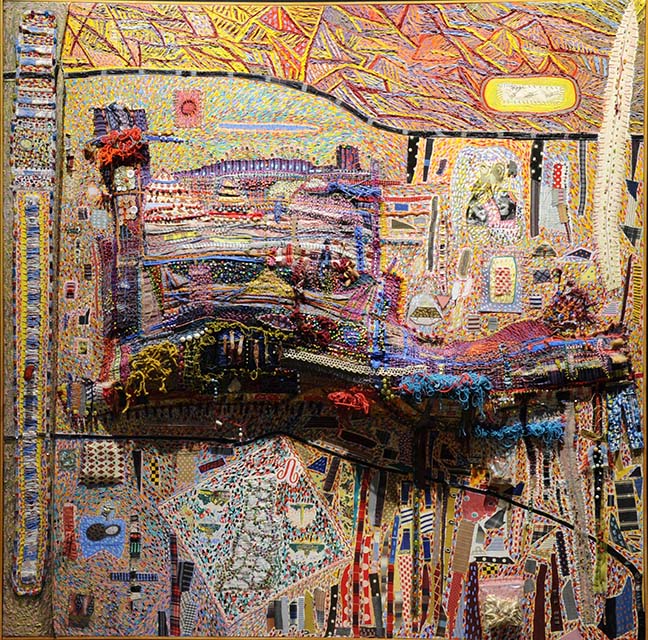

There was a painting in my retrospective called Whole Cloth, like the expression “you’re making something up whole cloth.” This was done in the nineteen-eighties when I was showing at Phyllis Kind Gallery. There was a lot of embroidery work and other things attached, coming out of the painting… these embroidery pieces I had done became 3D when I attached them to the canvas.

“Whole Cloth,” mixed media on canvas, 60.5” x 60.5” x 6”, 1984

“Whole Cloth,” mixed media on canvas, 60.5” x 60.5” x 6”, 1984

DR: You went on from there and did some sculptures that were related to those paintings in some way. They were wrapped in fabric and were sort of like tribal fetish objects.

MFN: Right, those objects took me into sculpture. I was already doing wrapped pieces that were connected [to the paintings]. I think one of the first pieces that was free standing was called Long Life. I actually took all these socks that belonged to my husband, back when I was married… you know how you’re supposed to darn socks if you’re a good wife. I had all these socks that I never darned and I stuffed them with old clothes and darned them together into a long painted and stitched, snake-like form, and called it Long Life. I wound it up like a huge nest on the floor and I also showed it with one end suspended from the ceiling, as if it was coming out of its coil.

DR: Many of your sculptural works seem to be vessels of one sort or another literally or metaphorically, is that accurate?

MFN: Right. Even some of my 2D works are related to the idea of vessels.

DR: Can you talk about that a bit? What are they containing?

“Secretions,” stoneware, installation view, dimensions variable, 1992-1999, detail of installation “Michele Feder-Nadoff: Between Heaven and Earth (1976-2013)”

“Secretions,” stoneware, installation view, dimensions variable, 1992-1999, detail of installation “Michele Feder-Nadoff: Between Heaven and Earth (1976-2013)”

MFN: One way to answer that is to say that it’s about lines. One aspect of the drawings that I do… is more about the containment of nothing. It’s not “nothing” anymore, I’ve drawn a line around it.

DR: Containing the nothing…

MFN: Yeah, if you think about the shapes in the drawings… when I do that loop. It also comes from the basic embroidery stitch or even a knitting stitch and also Arabic and Hebrew [writing]. It condenses a lot of gestures. Most of the time, I’m just wrapping that line around blank paper. The drawing become activated because of the gesture inscribing or going around empty space, and it’s the viewer’s visual perception that makes that blank space be something. The idea of nothing is really not about nothing — but the edge between something that is there and not there. It ‘s about capturing light.

“Benjamin Notebook 2,” gouache and sumi ink, Chayah series, 8.5” x 10.75”, 2017

“Benjamin Notebook 2,” gouache and sumi ink, Chayah series, 8.5” x 10.75”, 2017

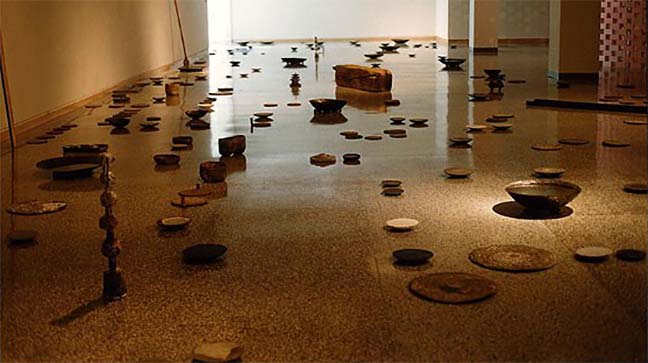

In the vessels that are actually like containers, I’m always doing it with the idea that the container is containing a void. Do you remember a series I did that was called Darshan? I did these castings, hundreds of them. I cast an iron bowl that was cast from a wooden bowl and in there, I cast over a hundred forms in copper, aluminum, bronze, plaster and wax… and it was the void. That was what that piece was about.

“Darshan” (offering), installation view, cast copper, aluminum, bronze, wax and plaster, dimensions variable, circa 1996

“Darshan” (offering), installation view, cast copper, aluminum, bronze, wax and plaster, dimensions variable, circa 1996

DR: In your writing you mention the performative aspect of your work; can you elaborate on that?

MFN: I have always been aware of the conceptual aspect, and of the fact that how I was making things was part of the work in a very conscious kind of way. I got frustrated when I was doing work that had a lot of texture and color and everything… I think part of the reason I stopped doing that [work] is that people couldn’t get past all that. They couldn’t see the conceptual part of it. These paintings would have different ways to represent and use imagery; I was really conscious of the mechanisms that we use to represent or express ourselves… it was really conscious, it wasn’t just a rush of emotion coming out. So, the performative aspect, for me, is a reflective performative aspect that just became more and more evident the leaner I made my work, and eventually I actually started doing performances.

DR: Were you influenced by the writings of John Dewey? I was thinking about his ideas about art as experience and the performance of making things and how the experience of that was his way of connecting art and craft together as part of a sort of continuum.

MFN: It’s not about art and craft being a continuum, though I agree with that. It was more about the idea that making something is thinking something. Making it, you’re not just having a gush and things are coming out, that you’re in what they call “the flow.” It’s that you’re making something that you’re thinking. I was always aware of the performative in the sense that you’re performing a tangible act, but the performed tangible act also evokes things, so it’s more than what it is.

DR: For a number of years you have apprenticed with traditional coppersmiths in Santa Clara del Cobre in Mexico. How has that experience influenced your work?

Deepening the copper tejo, Taller Ziranda, Santa Clara del Cobre, Michoacán, México

Deepening the copper tejo, Taller Ziranda, Santa Clara del Cobre, Michoacán, México

MFN: Well, the big thing that it did was that when I came back from my first trip [to Mexico] in 1997, I ended up opening up my studio and working with a lot of people in the neighborhood, and many were from immigrant communities. My studio became a community space from 1998 until I left for my Fulbright in 2010. It totally changed my frame of being an artist. Instead of being totally focused on just myself and my own work, I started to think about artistic production as a sort of life production. It revived a social consciousness that I had pretty much given up when I went to art school. I’m still resolving some of the tensions between working by myself and working in communities, and what I want to do with that and how I want to contribute to things.

DR: What are your thoughts about cross-cultural influences? I was just thinking about how when working in Mexico you are coming from one culture to another and you’re influencing and being influenced by it… OK, let me ask you the next question, because maybe that will clarify things.

MFN: Can I say something about that though…

DR: Sure.

MFN: I can tell you that just going to the Art Institute was that for me. I came from a really Orthodox background where you weren’t even supposed to go out with someone who wasn’t Jewish. It was the first time in my life that I was in a secular environment, though I was a rebel and didn’t quite fit in or feel comfortable in the environment I was raised in. I first experienced the whole challenge of dealing with a different cultural environment when I went to SAIC. I think the reason I could come to Mexico was, in part, my own background. The community I work with in Mexico is also a very religious community, a very devout community. They are people of faith; they know what it is to have sacred and non-sacred time. They have a different perspective on things.

DR: Well, let me ask you another question, and I’m not trying to sandbag you. Lately there has been a lot of criticism and even hostility directed to what is perceived to be “cultural colonialism.” How does an artist “do it right,” when interacting with or riffing on another culture? Or, do you feel that this criticism is unwarranted?

MFN: No, I think that’s a totally valid criticism, but it also relates to a general thing that’s happening in art. I could have done that when I first went to Santa Clara; I could have come back and done sexy work that was inspired by the indigenous or whatever, but that was never my intention. In the art world there’s more and more of a division between artists who make things and artists who have power and want to flaunt their power, who have other people make things for them. I think that going to other cultures to get inspiration, you know, like they say that Picasso went and looked at African masks… I don’t think there’s anything wrong with people being inspired. I think that what’s wrong is when you take the power, or make money from that, or make people anonymous and steal things from them.

More and more in the art world, the division between [the concept and the making] is part of what makes the work valuable. I think the whole art world is colonial, the whole way it functions. In my work, part of what I’ve been trying to do is to say that there’s a field of makers in this world… everyone, the tortilla maker, the person who’s making good coffee for you is a maker, everyone is a maker. What does it mean to give people who make things credit and see that they are paid fairly? I mean… there’s so much injustice. If you think about the visibility and invisibility factors involved and who’s appropriating who… and so I think that colonialism is not just about being inspired by styles, it’s what you do with that too.

I have been inspired by working in Santa Clara. [When I had] my show in Rockford, I told them that I wanted to have one part of the show dedicated to promoting those artisans. They didn’t want to do it and I had to fight to get them to do it.

“Snake Coiled Vessel,“ Antonio Ziranda, forged and etched copper, 37 x 40 cm. 1988, collection Museo Nacional de Cobre

“Snake Coiled Vessel,“ Antonio Ziranda, forged and etched copper, 37 x 40 cm. 1988, collection Museo Nacional de Cobre

“Three birds,” Maestro Jesús Pérez Ornelas, hammered and engraved copper, 1999

“Three birds,” Maestro Jesús Pérez Ornelas, hammered and engraved copper, 1999

DR: What is the role of religious thinking and spirituality in your work?

MFN: I don’t really feel comfortable talking about that. (Conversation continued off the record.)

In Judaism there is this idea that you do actions in the world and they can be transformative… I bring a lot of social-political-philosophical thought to what I do. The kind of intensity I have about it – I’m sure that has to do with my background.

DR: Can you talk a bit about your “mole theory” and the importance of body awareness and touch in art making?

MFN: Mole theory is a humorous term [I chose] to reference the haptic, the complete sensory perception that makes us move as artists when we make things. It is a phenomena and a dynamic I am still researching in my drawings and [my] anthropological work. It has to do with how gesture and speech, language and making are connected, are a bridge to cognition all merged together. It is a blind seeing through the body.

I first started to realize that when I did an installation in Rockford… basically one half of the whole space, and I had hundreds of pieces. It was a whole walk-through installation, mostly on the floor. What happened was, as I unwrapped each piece, I followed the mole theory. [Something] inside my body told me where to go and where to put the piece down. We’re talking about a huge amount of space and a huge number of pieces. I can’t remember what my original plan was… I didn’t follow the original plan and what resulted, I was totally happy with.

“Homage to Santa Clara,” installation view, cast bronze, aluminum, copper, plaster and wax; carved wood, 2003

“Homage to Santa Clara,” installation view, cast bronze, aluminum, copper, plaster and wax; carved wood, 2003

It was such an intense experience; I was basically hallucinating by the end. I was supposed to drive home, but ended up staying in a hotel. I was so intense in doing it that my vision was not in reality. I couldn’t see… I was seeing this other thing. It was this inner thing that was connecting all the perceptions I had; it wasn’t just from my optical sensations.

DR: What are you currently working on and where do you think your work is headed in the future?

MFN: My practice has evolved to one that is itinerant; it has to be portable. My installations have always been a way to bring the work to completion on a grand scale. Now, it’s like the world is my studio. What I want to do next is work in frescoes, in rooms and spaces [that] I can work in performatively, so that the creation of the work, the cumulative daily practice is accessible to visitors. In the last several years it has been my dream to have a space that I work in and fill but pass on. It either becomes obliterated after being experienced by others or remains, permanent or impermanent.

Working outside on mural size frescoes [also means] making the making of the fresco public. Fresco means many things here in Mexico… it is political as in many ways [it is] in Chicago and other cities, but I also am interested in fresco as it goes back [to] the first paintings found in caves. [It is] based in the first gestures of expression, or evidence of humans’ need to register their gestures and marks. So this is what I want to work on next, while continuing my daily practice of drawing in notebooks and [on] sheets of paper. It is definitely an itinerant, “ambulant” process. I live right now as a turtle with my home being my own body. I am not settled.

“The Regeneration of Death,” sumi ink, wood, detail of “Soundings” installation, 2011

“The Regeneration of Death,” sumi ink, wood, detail of “Soundings” installation, 2011

“Lotus and Floating Lotus.” in installation, “Ofrenda a Santa Clara,” hammered and forged copper, table, pine needles, and water. 48” x 48” x 14”, 2011

“Lotus and Floating Lotus.” in installation, “Ofrenda a Santa Clara,” hammered and forged copper, table, pine needles, and water. 48” x 48” x 14”, 2011

Detail, “Golems,” wax, human hair, mixed media, largest H 73.5” – smallest 7.5”, 1986

Detail, “Golems,” wax, human hair, mixed media, largest H 73.5” – smallest 7.5”, 1986

“Chayah (mayiim chayiim),” detail of installation “Michele Feder-Nadoff: Without End (ein sof),”Brauer Museum of Art, 2012-2013

“Chayah (mayiim chayiim),” detail of installation “Michele Feder-Nadoff: Without End (ein sof),”Brauer Museum of Art, 2012-2013

“Chaya – Lotus,” 23.5” x 15.5”, sumi ink and gouache on Mexican handmade amate (bark) paper, 2017

“Chaya – Lotus,” 23.5” x 15.5”, sumi ink and gouache on Mexican handmade amate (bark) paper, 2017

“Benjamin Notebook 3” Chaya series, gouache and sumi ink, 8.5” x 10.75”, 2017

“Benjamin Notebook 3” Chaya series, gouache and sumi ink, 8.5” x 10.75”, 2017

Detail of installation, “Michele Feder-Nadoff: Between Heaven and Earth (1976-2013),” hammered copper, stoneware, porcelain, cast bronze, Rockford Art Museum

Detail of installation, “Michele Feder-Nadoff: Between Heaven and Earth (1976-2013),” hammered copper, stoneware, porcelain, cast bronze, Rockford Art Museum

Michele Feder-Nadoff, during the performance of “Passing” with collaborator Kanaan-Kanaan, Western Oregon University, 2012. (Photo Western Oregon University).

Michele Feder-Nadoff, during the performance of “Passing” with collaborator Kanaan-Kanaan, Western Oregon University, 2012. (Photo Western Oregon University).

Top Image:

“Akko/ Akka,” sumi ink, gouache, etchings, rubbings, on collaged Japanese papers, 7 x 12 feet, 2012, in installation “Between Heaven and Earth (1976-2013)

Michele Feder-Nadoff is an artist and anthropologist who currently resides in Mexico City, Mexico. She received her doctorate in Social Sciences from El Colegio de Michoacán, Mexico in 2017. She also holds BFA (1977) and MFA (1979) degrees from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She was a Fulbright Scholar in Mexico in 2010-2011 and has received grants from the Illinois Arts Council, the Rockefeller Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts and many others. Her work has been represented by Phyllis Kind, Jan Cicero and Tough galleries, and can be found in private and public collections, including the Illinois State Museum, DePaul University Museum of Art, Figge Museum of Art and the Elmhurst Art Museum.

El Charon Family Forge and Workshop

This family studio in Santa Clara del Cobre was founded by Grand Maestro Jesus Pérez Ornelas (1926-2014) when he became independent of his father don Bernardo Farfán who had his own forge-workshop across the street, dedicated to making copper cauldrons. Maestro Pérez is considered one of the three pillars and “living legends” of Santa Clara along with his good friends, the artisans Maestro Etelberto Ramírez Tinoco (1944-1993) and Maestro Feliz Parra Espino (1926-). They were known affectionately as the “three musketeers.” Pérez was known for his imaginative extremely detailed copper vessels often taking figurative-shapes, such as his “three bird” pieces (see illus. above). Since his passing in 2014, the studio has been run by three of his sons: Jaime Pérez Pamatz, José Sagrario Pérez Pamatz and Napoleón Pérez Pamatz (Facebook – Napoleon Perez). They are known for their distinct styles and for following their father’s tradition of excellence in producing vessels with birds and animals as well as abstract forms and other works.